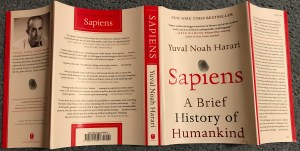

In the book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Harari discusses several thought-provoking aspects of human history. One of the most fascinating and far reaching developments is what he describes as “common myths.” He gives the following introductory description of this concept in his discussion of key developments from the Cognitive Revolution:

“Any large-scale human cooperation – whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe – is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination. Churches are rooted in common religious myths. … States are rooted in common national myths. … Judicial systems are rooted in common legal myths. ….

“Yet none of these things exists outside the stories that people invent and tell one another. There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings.”

Based on his description, all of the vagaries and debates that philosophers have waged since the Cognitive Revolution occurred can be chalked up to fiction. In the modern world beyond the list above, organizational constructs such as corporations would also qualify as common myths that are accepted by our collective imaginations.

Given that Sapiens, like other great apes, need to cooperate to survive, the advent of common myths may well be an evolutionary development that gives us a survival advantage, but that still doesn’t make these myths any less fictitious. They are unique to Sapiens imagination though. Common myths require the use of fictive language. Without that means of communication, a common myth cannot be conceived or sustained.

Harari draws a distinction between a common myth and a lie. He claims that many animals lie, and there’s nothing special about being able to do so. For example, lying as a diversion has been observed in other primate societies beyond Sapiens as a means to steal food from competitors. The power of a common myth in Sapiens society comes from the ability to create an imagined reality that is so widespread.

Common myths are passed on to each new generation via parent to child, and through societal influences, and as such, they allow cooperation on a grand scale. These common myths, along with a person’s experience, are the basis for shaping that person’s worldview. Instead of maxing out at around 150 individuals (the practical limit prior to the Cognitive Revolution that Harari points out in his book), millions, or even billions of Sapiens can now live together and cooperate within a single society in the modern world, at least until their worldviews clash in a catastrophic way. The fact that these worldviews can collide so spectacularly – different religions clashing; different factions challenging the rule of law or governmental authority; different factions challenging national boundaries – demonstrates the fictional content of each on some level.

As a thought experiment, one might wonder what would happen to a modern Sapiens were they able to thrive without being influenced at all by any existing common myths. What worldview would they hold? Would this be a way to definitively separate fact from common myth fiction?

There is a widespread fascination with the idea of feral children as discussed in this Guardian article from April 2017. In it, the author discusses why various reports about children being raised by wolves or other non-human animals are intriguing even though they were found to be fictionalized. Even with the mundane explanations of what really happened to these children, they point to one thing that is inescapable. Sapiens are incredibly adaptable. A child will mirror its companions, whoever or whatever they may be. In a normal environment, that would imply, at least initially, they would adopt the worldview of whoever or whatever taught them about the world. From there, the degree to which they would expand or distort that worldview would be dependent on their cognitive abilities (including their level of imagination) and their opportunity. The one thing that even the mundane explanations regarding feral children support is the influence of nurture over nature, and by extension, the inescapable power our common myths hold over us. Then again, a particularly resourceful group can also leverage great power over the common myths, changing them, growing them, and exerting undue influence over huge numbers of people and the world.

Harari sums up his discussion on the topic nicely:

“Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have thus been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today, the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.”

Who knew that we all lived in the world of science fiction? By virtue of our common myths, we share multiple realities – some objectively real; some imaginary – as a matter of course.

References:

Book Review: ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’ – a story of where we came from and where we might be going

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Harper, by Yuval Noah Harari

Summary: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

Also by Yuval Noah Harari:

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harper, by Yuval Noah Harari

[…] A Brief History of Humankind’ – a story of where we came from and where we might be going Follow-on thoughts about ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’ – Part 1: Common Myths Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Harper, by Yuval Noah Harari Summary: Sapiens: A Brief […]

LikeLike

[…] Follow-on thoughts about ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’ – Part 1: Common Myths […]

LikeLike

[…] Noah Harari observed. In his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, he introduced the idea of common myths, upon which all of our modern societies are based, suggesting these myths may have primed us all to […]

LikeLike

[…] and book reviews including What is reality?, The God Delusion – Why limit our perception?, and Common Myths. Our common myths form the foundation of human society. Our laws codify them. The ongoing legal […]

LikeLike

[…] A Brief History of Humankind’ – a story of where we came from and where we might be going Common Myths Preparing the world for the next pandemic Climate Change May Make Pandemics More Common Doctors […]

LikeLike

[…] Common myths Climate crisis Too many people Less competition, more cooperation Novel Coronavirus 2019 UN History We are living with a modern ‘Lord of the Flies’ style threat The world I want to live in Too many people Biodiversity What is reality? Translation at the UN The Animal Kingdom includes us […]

LikeLike

[…] https://agoodreedreview.com/2017/05/26/book-review-sapiens-humankind/ https://agoodreedreview.com/2017/05/30/sapiens-thoughts-common-myths/ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/imagination […]

LikeLike